There is an apparent paradox in the relative values of water and diamonds, which has been analysed by numerous authors over the centuries, including Plato, Adam Smith and John Locke. This so-called “paradox of value” notes that while water is essential to life and diamonds are not, the market price of diamonds is strangely far higher than that of water.

A trivial challenge to the conventional explanations from economists, is that the units chosen to measure each commodity are arbitrarily chosen and possibly misleading. The volume of diamonds is typically one diamond where most people will conceive of it as being the size we might encounter on a piece of jewellery; the possibility of a microscopic fragment of tetrahedral carbon lattice is overlooked. Similarly the volume of water is conceived as a glassful or a bucketful, rather than the size of a major river or ocean. If we were to be able to purchase the River Thames or the Hudson River for the price of a jewellery diamond, we might regard that as a bargain, and that water would be worth more than diamonds, even though water is abundant. But this challenge is nitpicking relative to the substance of the paradox.

The Vending Machine in the Desert

Let us instead consider an example: suppose we are alone in the middle of a desert, accompanied by a solar-powered camel, upon which we can ride back to civilisation in exactly two days. We know that to avoid dying of thirst, we need exactly three litres of water per day. In front of us is an amazing vending machine (which cannot be stolen or broken into). The vending machine has two slots in it. If we put a litre bottle of water into one slot, we will receive an engagement ring sized diamond. If we put such a diamond into the other slot, we will receive a litre bottle of water.

Let us consider our options, with varying levels of prior resources available to us.

The first thing we notice is that if the sum total of our current diamonds and water bottles is less than six, then we are going to die.

Suppose instead that we start with 20 diamonds and no water bottles: what will we do? Clearly we should put 6 diamonds into the machine, get 6 water bottles, and then jump on the camel and ride home. When we get home, we will be poorer but not dead; we will still have 14 diamonds, and water is abundant there. Because water is abundant there, we would not trade any further diamonds for water.

Consider our emotional state as we feed diamonds into the desert machine. Seeing the first water bottle makes us pleased: the machine really works! The second to fifth bottles are each as gratifying as each other. But the appearance of the sixth bottle is the one that truly makes us happy: we are definitely not going to die now.

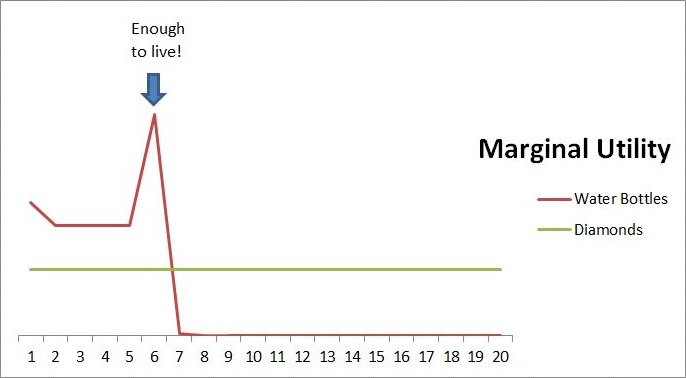

Contrary to the notions of marginalists, the sixth bottle of water does not have less utility to us, than the fifth or the second. Clearly it has more, because the sixth bottle is the one which is the difference between life and death; we die with 5 but live with 6.

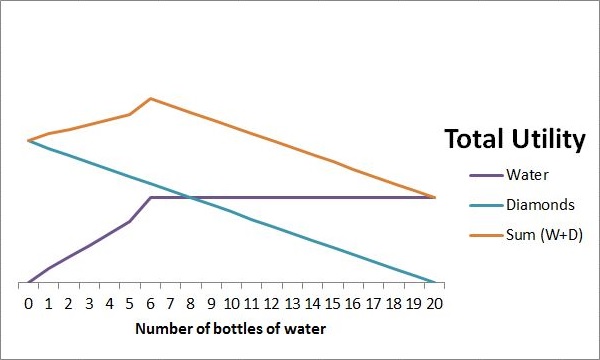

Each of these six water bottles are worth more to us than the diamond we exchanged for them. In considering how many diamonds to put in the machine, it is the total utility of the water bottles which matters to us, rather than the marginal utility: is the total at least 6?

If the machine jammed briefly, when we put the sixth diamond in, we would have no hesitation in putting in a seventh diamond if that’s what it took to get the sixth bottle of water out.

What happens instead, if we start with 20 water bottles and no diamonds? The optimal solution is to put 14 of the water bottles into the machine in exchange for diamonds, and then ride home, again with 14 diamonds and 6 water bottles.

Six bottles of water is the number which optimises total utility. The graph of individual marginal utility is not a negative slope, it is a cliff: flat on the top, vertical at the edge, and flat again at zero. The cliff edge discontinuity occurs at the number of units equal to “enough”.

How high the spike at the edge of the cliff is, will depend on how stark the difference in outcome is, between “not enough” and “enough”. If we were acquiring players for a game of bridge, getting the fourth player is nice, but not a matter of life and death. So the spike in utility for getting a fourth player would be less high.

Having noted all this, the apparent paradox of diamonds and water disappears. Water is worth more than diamonds, when we do not have enough water (left side of the graph). Diamonds are worth more than water in every other context (right side of the graph).

The Cautious Traveller

A more cautious desert traveller might consider the possibility of travelling with an extra water bottle “just in case”. Perhaps they might accidentally drop a bottle while drinking, or the solar-powered camel might slow down or break down? So they might choose to forego the fourteenth diamond and take a seventh bottle of water from the vending machine.

This seventh bottle of water is clearly less useful than the sixth bottle, because it is not directly keeping the traveller alive. It only becomes useful in the event of some kind of accident. But its usefulness is more than zero, in terms of peace of mind, even if the anticipated accident does not occur. Specifically it has a distinct purpose from the purpose of the first six bottles.

If we were to show this on a marginal utility graph, there would now be a ledge on the cliff face. In the diagram below, I have chosen to show the cautious traveller taking two spare bottles of water (to avoid getting spurious results from choosing only one discrete unit of anything). The width of the ledge is how many spare bottles get taken. The height of the ledge is subjectively how useful the traveller thinks the spare bottles will be. If the traveller decides the extra bottles are less useful than the diamonds, then they will keep the diamonds instead.

The only reason there is a ledge at all, is because we have introduced a second purpose or usage for the goods in question. To generalise, there will be as many ledges in the marginal utility graph as there are additional discrete purposes. If we include the clifftop plateau as a kind of ledge, then there are as many ledges as purposes.

The individual marginal utility graph for a product with multiple purposes will look like a series of steps. It only becomes a negative sloping line if we insouciantly choose that the quantity associated with each additional purpose is exactly one of whatever unit of measurement we are using. If our cautious traveller chose one extra litre to take, then my graph above would have a section between 6 and 8 bottles which would look like a negative sloping line. However, if we changed the horizontal scale to milli-litres instead of litres, then the step reappears between 6001 milli-litres and 7000, with a cliff at 7001 down to zero.

If there were enough discrete uses for the same product, we might be tempted to abstract that series of steps into a negative sloping line. But in doing so, we are obscuring the equal utility of identical units acquired for an identical purpose.

It is only when the steps of the individual utility graphs are aggregated together across many purchasers, that the negative sloping demand curve legitimately appears.

Marginal Utility of Investment Goods

In the context of the thought experiment, I believe we are expected to treat diamonds as a self-evidently durable, scarce and valuable asset. In modern times, where we know about carats, cut, colour and clarity as differentiators, and the availability of artificial diamonds forcing down their market value, we might not choose diamonds as our exemplar.

Maybe a gold coin, like a sovereign or a krugerrand, is a better modern example to choose. Of no practical use as money, yet tradable almost anywhere for a high value. Unconsumed. Fungible. Portable.

I have have chosen to show the marginal utility of the diamonds as a horizontal line. If we accept that the diamonds (or our gold coins) are identical, perfectly durable, portable and valuable anywhere, why should the 100th diamond or coin be any less useful to us, than the first? The 100th coin will demand the same price as the 50th and the first. There is no discount below market value for buying in bulk!

Any variance in future value of the diamonds and gold has nothing to do with our present personal utility; it is the aggregate of the future personal utility of everyone else in the global market for these assets.

It is this estimate of the use-value of someone else for diamonds, which demolishes Plato and Adam Smith’s canard of differentiating between value-in-use and value-in-exchange.

More nitpicking:

Market value of water: does water have any market value at all, in the locations where it regularly falls out of the sky? It certainly costs some money to buy a bottle of water at the shops, but I think we are actually buying the bottle and the convenience, rather than the liquid itself, which can be had for nothing in restaurants and clubs. Similarly our water bill at home is really for the value of the pipework and sewage removal rather than for the liquid itself. Any domestic water usage charge is more about encouraging the avoidance of waste than a serious attempt at charging for the value of the liquid. If we do determine that water has some market value even when it is abundant, then the effect of that determination is tiny and inconsequential to the above analysis.